Sabbath and Early Christians, Part 1

According to the 1647’s Westminster Confession of Faith and the 1689’s London Baptist Confession of Faith, Sabbath observance is a positive, moral, and perpetual command binding all men in all ages but then says from Creation to Christ it was on the Seventh Day but changed into the First Day of the week from Christ to Consummation.

“As it is the law of nature, that, in general, a due proportion of time be set apart for the worship of God; so, in His Word, by a positive, moral, and perpetual commandment binding all men in all ages, He hath particularly appointed one day in seven, for a Sabbath, to be kept holy unto Him: which, from the beginning of the world to the resurrection of Christ, was the last day of the week, and, from the resurrection of Christ, was changed into the first day of the week, which, in Scripture, is called the Lord’s Day ; and is to be continued to the end of the world, as the Christian Sabbath”

If Sabbath observance as they say is a positive, moral, and perpetual command then it is that important and must have found a place of prominence among the early Christian writers. Not to say that their letters are infallible, nevertheless, let us test this claim by doing a brief survey of what the following ancient writers taught about the Sabbath and perhaps the Mosaic Law and the New Covenant.

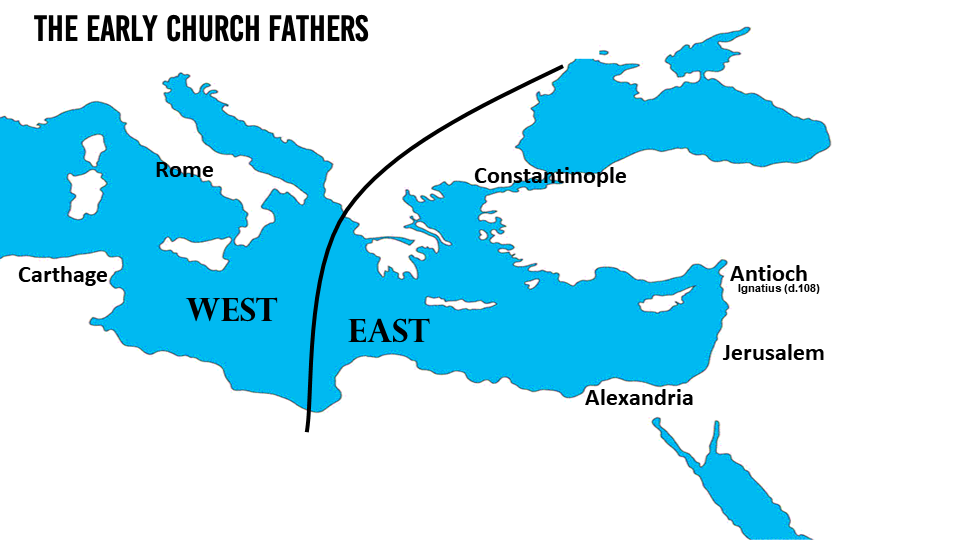

Ignatius of Antioch (50 – 108 AD)

Justin Martyr (100 – 165 AD)

Tertullian (160 – 220 AD)

John Chrysostom (349 – 407 AD)

Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 AD)

Unless otherwise specified, all Scripture quote is from the New International Version 2011. And all quotes from the ancient writers is taken from the New Advent, a Roman Catholic Online Encyclopedia.

Part 1 – Ignatius of Antioch (50 – 108 AD)

Ignatius was known to have ministered in Antioch, and like Paul, he was a Roman citizen who, according to tradition, was also put to death for his faith. There are seven letters under his name but will take a peek in his three epistles where the Sabbath and perhaps the Law and even the New Covenant are mentioned.

In his Epistle to the Romans, he writes as if his epistle serves as a preface, an introduction to Apostle Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. There he described its character, contents, arrangement, authenticity, integrity, date, and circumstances of composition.

In it he said, “was out and out a Jew, and that his whole training accustomed him to adopt the standpoint of the Law—the more so as the revelation of the Old Testament is in the last instance the basis of the New Testament... Paul is dealing, not with the Jewish Christians, but with the Jews still subject to the Law and not yet freed by the grace of Christ.” Intimating, therefore, that Christians are freed from the Mosaic Law by the grace of Christ. He also said Paul, “has no toleration for insistence on the practice of the Law within the Christian fold,” and that, “the spirit of Judaism is not compatible with the Spirit of Christ and the Divine election to grace.”

In his Epistle to the Philadelphians, which is shorter than John’s First Epistle, he warned the believers there not to listen to those who preach the Jewish law referring to their teachings as, “wicked devices and snares of the prince of this world.”

Finally, in his Epistle to the Magnesians, which is pretty much of the same size as his Epistle to the Philadephians, he begins by mentioning the law of Jesus Christ.

We then find him arguing against being subjected to the Jewish law. He refers to those teachings as strange doctrines, old fables, unprofitable, and ancient order of things and then issues a clear dichotomy between Jewish law and grace saying, “For if we still live according to the Jewish law, we acknowledge that we have not received grace. For the divinest prophets lived according to Christ Jesus.” That these two cannot mix, “It is absurd to profess Christ Jesus, and to Judaize.”

He also rejected the observance of the Sabbath and advanced the observance of the Lord’s day, “For if we still live according to the Jewish law, we acknowledge that we have not received grace. For the divinest prophets lived according to Christ Jesus.”

However, he doesn’t ground the basis of such observance on Creation Rest but on the resurrection of Jesus Christ, “If, therefore, those who were brought up in the ancient order of things have come to the possession of a new hope, no longer observing the Sabbath, but living in the observance of the Lord’s Day, on which also our life has sprung up again by Him and by His death.”

The 1647 Westminster Convession of Faith Sec. 21.7 and the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith Sec. 22.7, they both say that the Sabbath was, “from the beginning of the world to the resurrection of Christ, was the last day of the week, and, from the resurrection of Christ, was changed into the first day of the week.” But this is clearly not what Ignatius of Antioch taught the early Christians. For Ignatius, Christians follow the principle of Christianity because they are under the Law of Christ, they observing the Lord’s day because the Sabbath has been discontinued. For Ignatius, the observance of the Lord’s day is not a continuation of the Sabbath which he finds to be an unprofitable, and ancient order of things.

For Ignatius, the believers follow the principle of Christianity because they are under the Law of Christ, they are observing the Lord’s day because the Sabbath has been discontinued. But the observance of the Lord’s day is not a continuation of the Sabbath which he finds to be part of an unprofitable, and ancient order of things.

Recent Comments